THE CLIMATE CRISIS AND ITS IMPACT ON CHILDREN’S RIGHTS IN IRELAND – This is a report that we as a group of young people submitted to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child in support of its State review of Ireland’s progress in implementing the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

This review happens every five years and the Committee asks for children and organisations representing children to share their views on how well children’s rights are being upheld. While many comprehensive reports were being written, as climate activists we felt the climate crisis was being ignored. So while the COVID pandemic kept us off the streets, we decided to get online and continue pushing for change by researching and drafting this report.

Who we are

Climate Rights Ireland is a group of young people working with the support of UNICEF to investigate how the climate crisis interacts with children’s rights in Ireland. We are a team of young people, led by young people, who created this report on behalf of young people to the Committee for the Rights of the Child. We hope this report will catalyse change and drive a shift in Ireland’s performance on the climate crisis and children’s rights.

What we want from this report

We have included key recommendations under each Article for the change the Irish government ought to deliver. Ultimately, we want systemic change that places the rights of children and the planet at the forefront. We want justice, equity, and a sustainable society. Our aim is that future reports do not need to highlight these issues and that this report can act as a mechanism for this change to be delivered.

Main Findings of the Report

The Rural-Urban Divide

In exploring the lived experience of children in Ireland regarding the climate crisis and the rural-urban divide, we found a disproportionate impact of the climate crisis on rural areas, and a need for the provision of necessary resources for those who are affected.

We consulted young people on:

- The impact of the climate crisis.

- Their access to resources and support.

- Their access to a just transition (a transition to a more sustainable world that protects those who are most vulnerable in society, like children).

The Impact of the Climate Crisis on Children in Rural Ireland.

Children living in rural areas disproportionately experience the impacts of the climate crisis

58% of rural respondents (Figure 1) had been impacted by the climate crisis, compared to just 21% of urban respondents (Figure 2), which shows us that rural children have been much more heavily impacted.

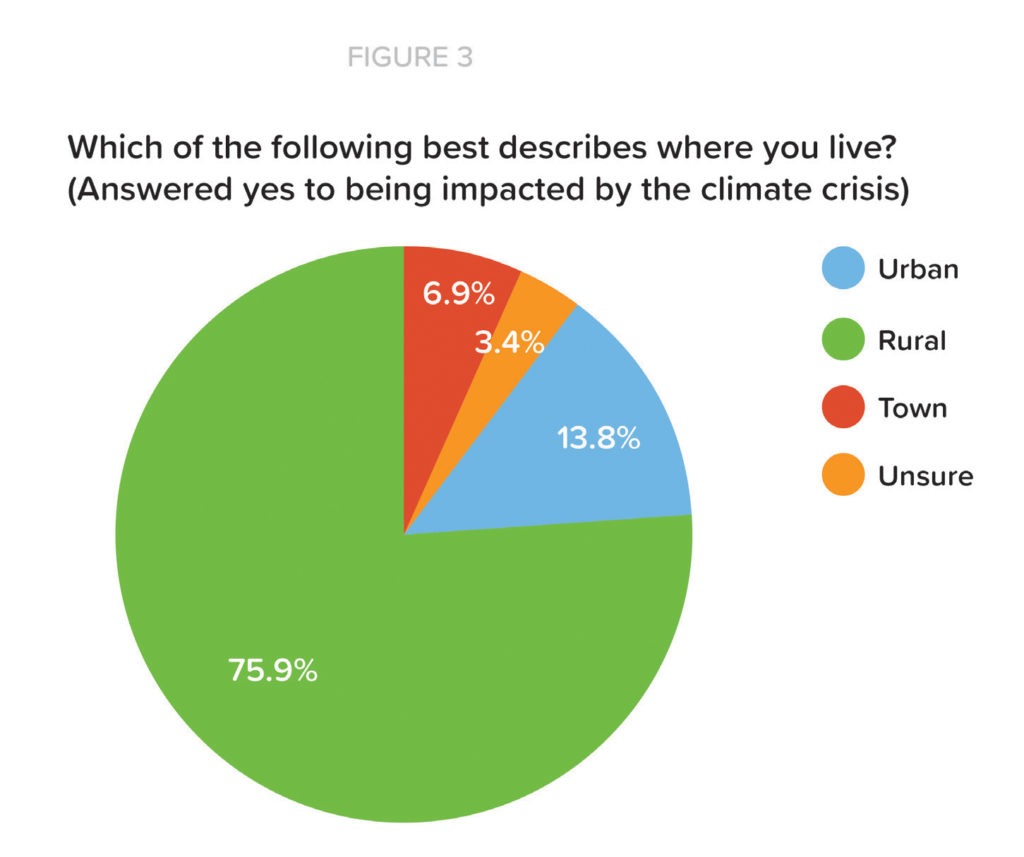

- Only 31.4% of Ireland’s population live in a rural area, but rural respondents made up over ¾ of the total respondents who said they had been impacted by the climate crisis (Figure 3), this is a disproportionate impact.

Support for young people in accessing resources and managing impacts

- We found a notable gap between rural and urban respondents in the level of support offered to achieve a just transition.

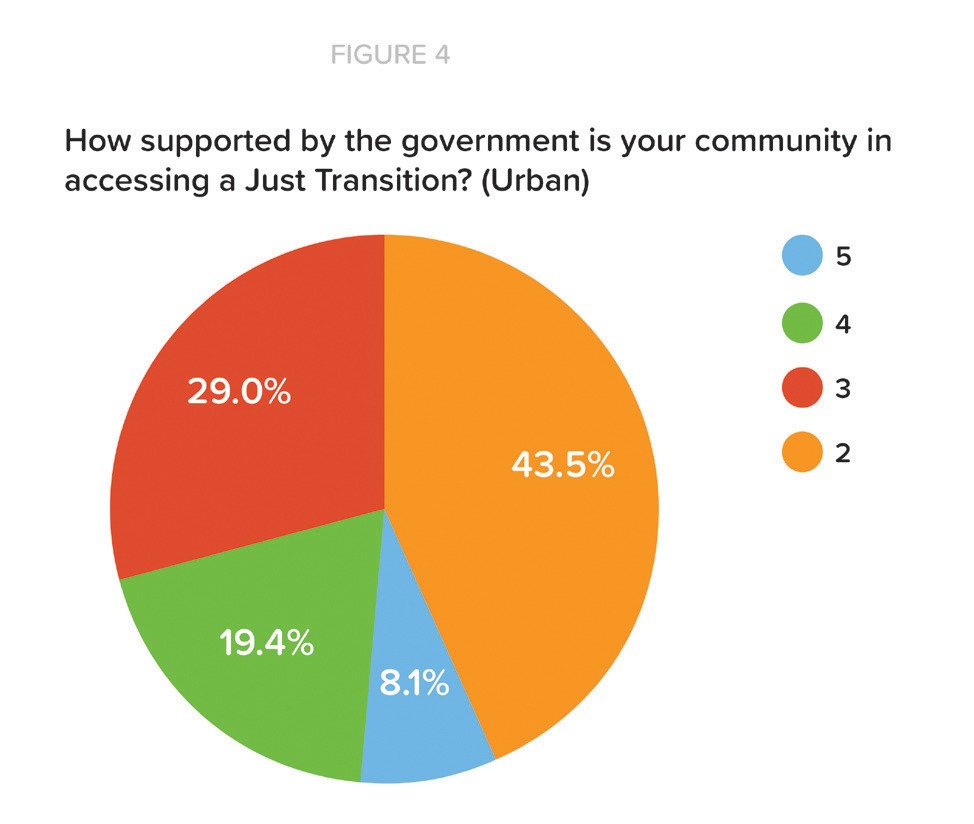

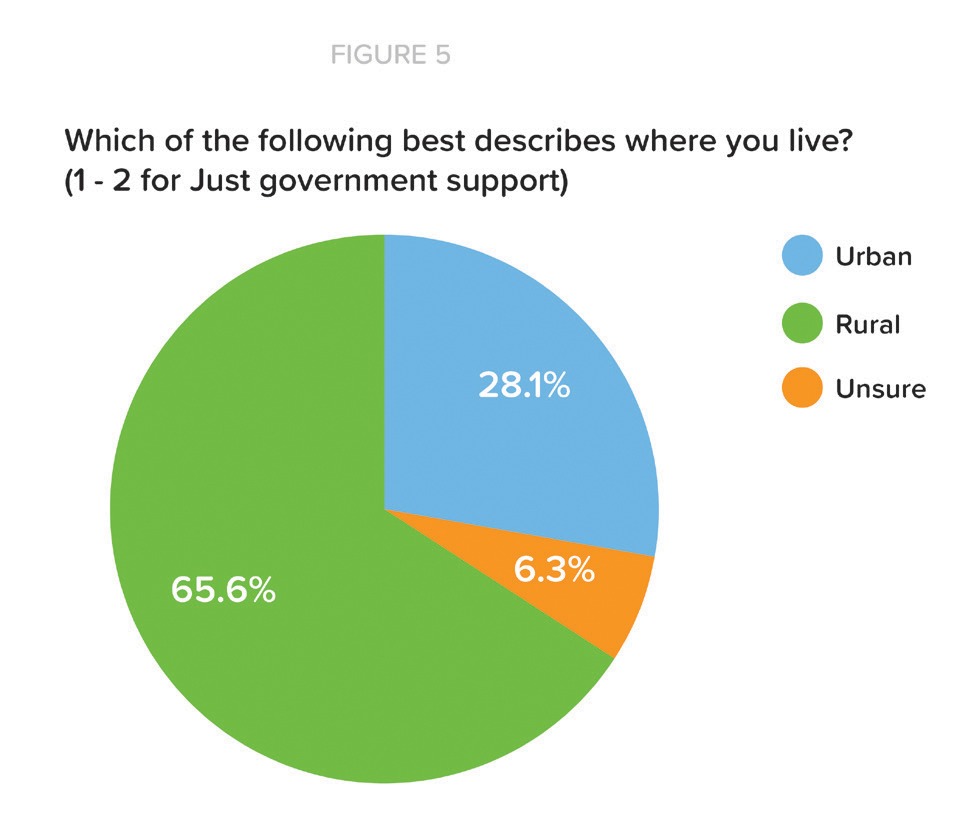

- 65.6% of those who rated the support offered to their community in the 1-2 (lowest) range were from rural areas. Not a single urban respondent gave a score of 1 (lowest). (Figures 4 and 5)

- One young person commented, “How can we have transitions to solutions that don’t even exist”.

- This is a particular issue for the farming community, “[there are] no grants which most people need, e.g small farmers cannot afford greener options”.

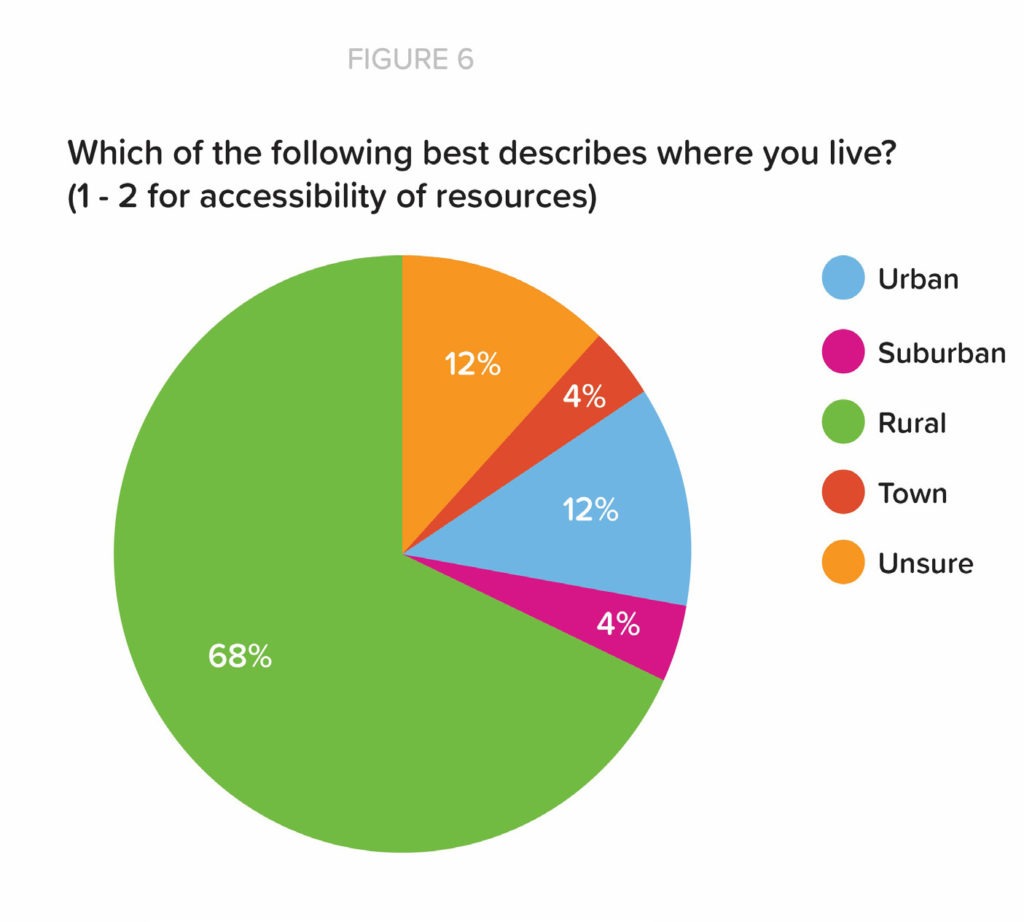

- There was another gap in how accessible resources were. 68% of respondents who reported inaccessible resources were from rural areas, compared to 4% in suburban and 12% in urban areas (Figure 6)

- “I live in a rural area and though we have the space for greener alternatives, we are never paid any heed, or given any options”.

- There are gaps in the quality of resources available, a participant noted that electric cars at petrol stations are “often broken, which turns people off switching to electric cars”.

- Furthermore, young people often have to find climate information from sources outside school. “[There are] not many physical resources but I am fortunate enough to have good WIFI and internet connection so I can find plenty of resources online.” When asked where they find information about the climate crisis one rural participant said ‘Only online and only if I seek them out myself’.

Recommendations

We believe our recommendations will work to reduce the disparity between rural and urban areas, and also increase the ability of children to access opportunities in education and employment.

- Transport

- We need comprehensive rural public transport infrastructure

- Ireland should work towards 15-minute cities that are walkable and accessible by public transport

- We should have increased pedestrianisation in cities

- Just Transition

- The government needs to meaningfully engage with and support rural Ireland.

- The government should economically incentivise sustainable farming and support the farming community

- The policy emphasis should be on corporations and those who are most responsible for the climate crisis.

- The government must engage with children in the Travelling Community.

- The government should provide more community resources such as bins, benches and cycle paths.

- There should be more accessible grants for electric cars and solar panels.

- The government should work on retraining workers and supporting continued employment in alternative and sustainable sectors.

- Education

- The government must implement Education for Sustainable Development.

- The government should introduce a TY module on climate action

- Education should focus on empowerment and developing key skills.

- Free third-level education should be provided.

- There must be comprehensive youth involvement in designing education, with youth voices at the forefront.

This includes increased flooding and extreme weather events such as Storm Ophelia, which participants stated negatively affect their everyday lives.

- One participant stated their crops are dying more frequently in Ireland’s heat waves.

- Another participant raised flooding in Cork City, and the negative effect on their sense of safety, the local economy and livelihoods.

- Participants described excess water waste during heatwaves and heating during “freezing winters”.

- Many participants also discussed increased anxiety as a result of these weather conditions.

Children outlined a negative impact on their mental health and sense of security resulting from this. This included:

- Feelings of anxiety

- A burden of responsibility

- A lack of climate action by the government

- A lack of adequate support

There were also fears about children’s future and development.

- They outlined feeling “helpless and hopeless”, stating “the future is honestly terrifying”

- Participants outlined that climate change has impacted their plans for the future. They are “unsure” of what the planet will look like, and stated, “climate change threatens the existence of their future”.

- Children asked “do I want to bring children into a world with climate change”

What we want from this report

We have included key recommendations under each Article for the change the Irish government ought to deliver. Ultimately, we want systemic change that places the rights of children and the planet at the forefront. We want justice, equity, and a sustainable society. Our aim is that future reports do not need to highlight these issues and that this report can act as a mechanism for this change to be delivered.